- Published on

Make your own container by hand from scratch without Docker

- Authors

-

-

- Name

- by Hamza El Idrissi

-

In articles and videos tutorials, you probably heard that containers described as “lightweight virtual machines” as a simplified explanation. This comparison helps beginners grasp the concept, but it misses the fundamental architecture that makes containers truly powerful; that’s why today we’ll try to craft a container from scratch, using only the basic tools available in Linux. So you’ll need a Linux system either on your local machine or through WSL (Windows Subsystem for Linux) if you’re on Windows. You can also use an Ubuntu image with Docker or any other container runtime, but for this article, we’ll be using my Ubuntu 22.04 LTS system.

What is a container?

Unlike virtual machines, which bring their own kernel and emulate entire hardware systems behavior, containers share the host’s kernel while creating isolated environments for applications. When I say isolated, I mean:

- Isolated filesystem: the container has its own filesystem, separate from the host’s filesystem. This is can be achieved

chrootcommand, which changes the root directory for the current running process and its children. This means that the containerized application can only see and access files within its own filesystem. - Isolated process space: the container has its own process space, meaning that processes running inside the container are isolated from those running on the host. This is achieved through Linux namespaces, which provide a way to create isolated environments for processes.

- Limited resources: containers should be limited in terms of CPU, memory, and other resources to prevent them from consuming too many resources on the host. This is achieved through cgroups (control groups), which allow you to limit and prioritize resource usage for processes.

chroot

Chroot (Change Root) is a Linux command that allows you to set the root directory of a new process. In our container use case, we just set the root directory to be where-ever the new container’s new root directory should be. And now the new container group of processes can’t see anything outside of it, it is in a confined environment often called “chroot jail,”, eliminating our security problem because the new process has no visibility outside of its new root.

Okay, let’s create a simple container using chroot and bash. We’ll create a minimal filesystem structure and run a bash shell inside it.

- Create a directory for the container: This will be the root directory for our container.

sudo mkdir -p /my-new-container- Inside the new folder, run:

sudo touch /my-new-container/hello.txt- now chroot the hell out of it:

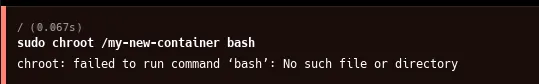

sudo chroot /my-new-container bashYou’ll see this error:

This error tells you it failed to run the command because it can’t find the bash executable. This is because the new root directory doesn’t have a bash executable or any other necessary files, and it can’t reach the host’s filesystem. So let’s fix that.

- Add bash executable: We need to copy the bash executable and its dependencies into the new root directory.

sudo mkdir /my-new-container/bin

sudo cp /bin/bash /bin/ls /my-new-container/bin/

sudo chroot /my-new-container bashIt will still fails, because even we copied the bash executable, it still needs some libraries to run. To find out which libraries are needed, we can use the ldd command, to list the shared libraries required by the bash executable.

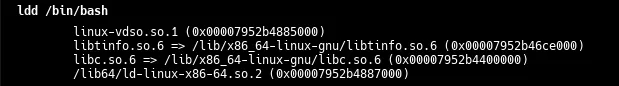

ldd /bin/bash

It will show this:

ldd /bin/bash

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007952b4885000)

libtinfo.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libtinfo.so.6 (0x00007952b46ce000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007952b4400000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007952b4887000)- Copy the required libraries: Now we need to copy the required libraries into the new root directory.

sudo mkdir -p /my-new-container/lib64

sudo mkdir -p /my-new-container/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu

sudo cp /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libtinfo.so.6 /my-new-container/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/

sudo cp /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 /my-new-container/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/

sudo cp /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 /my-new-container/lib64/- Now finally run the

chrootcommand again:

sudo chroot /my-new-container bashIt will work now, and you’ll see a new shell prompt. You are now inside the container, and you can run commands as if you were in a normal bash shell`

You’ll still need to copy other executables and libraries if you want to run other commands inside the container. For example, if you want to run

ls, you’ll need to copy thelsexecutable and its dependencies as well.

Namespaces

While with chroot, we isolated the filesystem of the new container, It still has significant limitations, you still can see processes, networks, or users; just run the following command:

ps auxYou’ll see all the processes running on the host system, and probably kill your container and this a major security issue. To solve this, we need some sort of process isolation, and this is where Linux namespaces come into play.

What are namespaces?

Namespaces are a feature of the Linux kernel. They are one of the core concepts of how Linux is built, and they allow you to create isolated environments for processes. Each namespace provides a different type of isolation, and they can be used together to create a complete container environment. Namespaces are used in containerization technologies like Docker and Kubernetes to provide process isolation, network isolation, and other features.

There are several types of namespaces, but the most relevant ones for our container use case are:

- PID namespace: This provides process isolation. Each PID namespace has its own set of process IDs, so processes in different namespaces can have the same PID without conflicting with each other.

- Network namespace: This provides network isolation. Each network namespace has its own network stack, including its own IP addresses, routing tables, and network interfaces.

- Mount namespace: This provides filesystem isolation. Each mount namespace has its own set of mount points, so processes in different namespaces can have different views of the filesystem.

- User namespace: This provides user and group ID isolation. Each user namespace has its own set of user and group IDs, so processes in different namespaces can have different user and group IDs.

How to create a namespace?

To create a namespace, we can use the unshare command. The unshare command allows you to run a program in a new namespace. For example, to create a new PID namespace and run a bash shell in it, you can use the following command:

sudo unshare --fork --pid --mount-proc bashThis command creates a new PID namespace and a new mount namespace, and it also mounts the /proc filesystem in the new namespace. The --fork option tells unshare to fork a new process, so you can run commands in the new namespace. Other options are:

--fork: Fork a new process in the new namespace.--pid: Create a new PID namespace.--mount-proc: Mount the/procfilesystem in the new namespace.--net: Create a new network namespace.--user: Create a new user namespace.--map-root-user: Map the root user in the new namespace to the current user.

How to use namespaces with chroot?

So now let’s create a chroot’d environment that’s isolated using namespaces

# from our chroot'd environment if you're still running it, if not skip this

exit

## Install debootstrap

sudo apt-get update -y

sudo apt-get install debootstrap -y

sudo debootstrap --variant=minbase jammy /better-root

# head into the new namespace'd, chroot'd environment

unshare --mount --uts --ipc --net --pid --fork --user --map-root-user chroot /better-root bash # this also chroot's for us

mount -t proc none /proc # process namespace

mount -t sysfs none /sys # filesystem

mount -t tmpfs none /tmp # filesystemHere is what we did:

- We installed

debootstrap, a tool that allows you to create a minimal Debian or Ubuntu filesystem. (It will download about 150MB and takes a few minutes to run. + it doesn’t cache the downloaded files, so it will download them every time you run it.)--variant=minbase: This option tellsdebootstrapto create a minimal base system.jammy: This is the codename for Ubuntu 22.04 LTS./better-root: This is the directory where the new filesystem will be created.

- We used

unshareto create a new namespace and run a bash shell in it. The options we used are:--mount: Create a new mount namespace.--uts: Create a new UTS namespace (for hostname and domain name).--ipc: Create a new IPC namespace (for inter-process communication).--net: Create a new network namespace.--pid: Create a new PID namespace.--fork: Fork a new process in the new namespace.--user: Create a new user namespace.--map-root-user: Map the root user in the new namespace to the current user.

- We used

chrootto change the root directory to the new filesystem we created withdebootstrap. mount: this commands mounts, meaning it creates a new filesystem in the new namespace. The options we used are:-t proc: This option tellsmountto create a new mount point for the/procfilesystem.none: This is the device name, which is not needed for the/procfilesystem./proc: This is the mount point for the/procfilesystem.-t sysfs: This option tellsmountto create a new mount point for the/sysfilesystem.-t tmpfs: This option tellsmountto create a new mount point for the/tmpfilesystem.

- Now you can run commands inside the new container environment. For example, you can run

lsto see the contents of the new root directory:

ls /cgroups

Now so far, we still got one problem to solve, which is resource isolation. We need to limit the resources that the container can use, such as CPU, memory, and disk I/O in order not to affect the host system. For this we will use cgroups (control groups).

What are cgroups?

Cgroups are a Linux kernel feature that limit, account for, and isolate the resource usage (CPU, memory, disk I/O, network, etc.) of a collection of processes. They allow you to move processes and their children into groups which then allow you to limit various aspects of them.

It’s important to highlight that cgroups were originally developed by Google engineers in 2006 and later merged into the Linux kernel in 2008. This technology has become a fundamental building block of all modern container systems.

How to use cgroups?

Let’s create a cgroup to limit the memory and CPU of our container. In modern Linux systems, cgroups are managed through the /sys/fs/cgroup directory. This is a special filesystem that allows you to create and manage cgroups.

- Create a new cgroup: First, let’s create a new cgroup for our container.

# Exit from our container if you're still in it

exit

# Create a new cgroup

sudo mkdir -p /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/mycontainer

sudo mkdir -p /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/mycontainer- Set resource limits: Now let’s set some limits for our container.

# Limit memory to 512MB

echo 536870912 | sudo tee /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/mycontainer/memory.limit_in_bytes

# Limit CPU to 30% of one core

echo 30000 | sudo tee /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/mycontainer/cpu.cfs_quota_us

echo 100000 | sudo tee /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/mycontainer/cpu.cfs_period_us- Add a process to the cgroup: Now we can add our container process to the cgroup.

# Start our container process

sudo unshare --mount --uts --ipc --net --pid --fork --user --map-root-user chroot /better-root bash &

# Get the PID of the container process

CONTAINER_PID=$!

# Add the process to the cgroups

echo $CONTAINER_PID | sudo tee /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/mycontainer/cgroup.procs

echo $CONTAINER_PID | sudo tee /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/mycontainer/cgroup.procsNow our container process is running with limited resources. It can only use 512MB of memory and 30% of one CPU core.

Testing our resource limits

To verify that our resource limits are working, we can try to exceed them and see what happens. Let’s try to allocate more memory than the limit we set:

# Inside our container

# Install a simple stress testing tool

apt-get update && apt-get install -y stress

# Try to allocate 1GB of memory

stress --vm 1 --vm-bytes 1G --timeout 60sYou should see that the process is killed due to memory overcommitment. This is because we limited the memory to 512MB, but the process tried to allocate 1GB.

Similarly, we can test the CPU limit by running a CPU-intensive task:

# Inside our container

# Run a CPU-intensive task

stress --cpu 4 --timeout 60sIf you monitor the CPU usage with top or htop on the host system, you’ll see that the process can’t use more than 30% of a CPU core.